Home » Nature

Dear Friends, Are you experiencing a barrage of COVID-19 emails, news broadcasts, articles, and posts? Like us, are you starting

Most interactions we have with wildlife can be described as one-sided. We see an animal, they see us and then

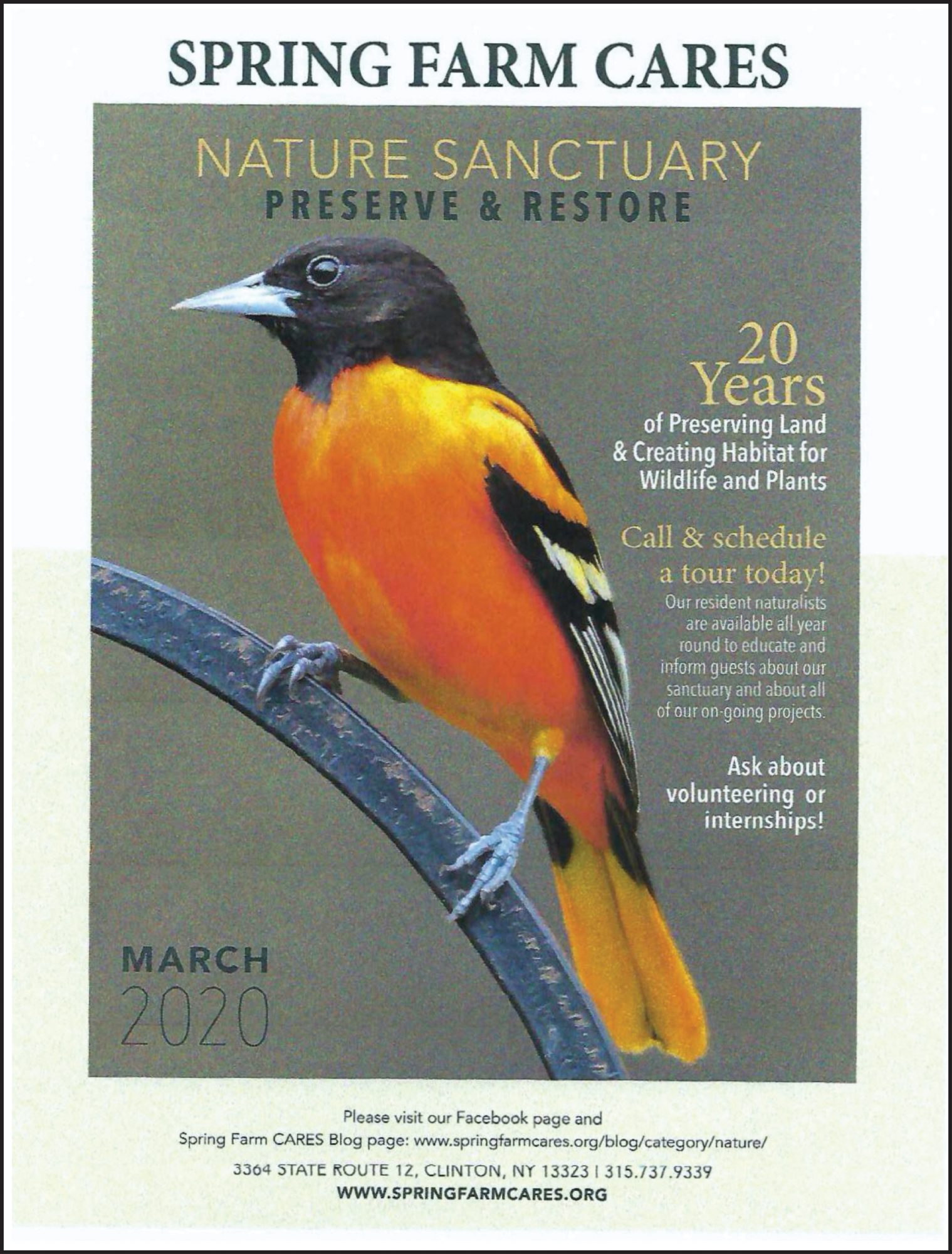

One of our foot trails at the nature sanctuary will forever be associated with a particular bird, a beautiful member

Wild Raptors Get Another Chance Reintroducing rehabilitated wildlife back into the wild can be tricky because sometimes a rehabber can’t